When the Liberation War of 1971 erupted, India’s involvement was hailed worldwide as the act of a benevolent neighbor coming to the rescue of millions of suffering Bengalis. This is the dominant narrative taught to generations, repeated in political speeches, and cemented in textbooks. But the hidden story beneath the surface tells a different tale. India’s actions, though decisive, were not motivated purely by compassion or solidarity. They were driven by calculation, strategy, and a cold assessment of national interest. The dark side of India’s involvement in 1971 is that it turned Bangladesh into a tool for its own geopolitical goals and, in doing so, sowed the seeds of dependency that still haunt Dhaka to this day.

India’s first motive was to break Pakistan apart. Since partition in 1947, Pakistan had been India’s bitter rival, both militarily and ideologically. By the late 1960s, Pakistan was growing closer to China and the United States, threatening India’s dominance in South Asia. When the Liberation War broke out, India saw its golden opportunity: by helping East Pakistan secede, Delhi could permanently weaken its archrival. This was not a sacrifice for Bangladesh but a strategy to achieve regional supremacy. The ten million refugees who crossed into India provided justification, but the refugee crisis was also leveraged as a political weapon to win international sympathy. India entered the war not because it suddenly discovered humanity, but because it saw the perfect chance to redraw the map of South Asia in its favor.

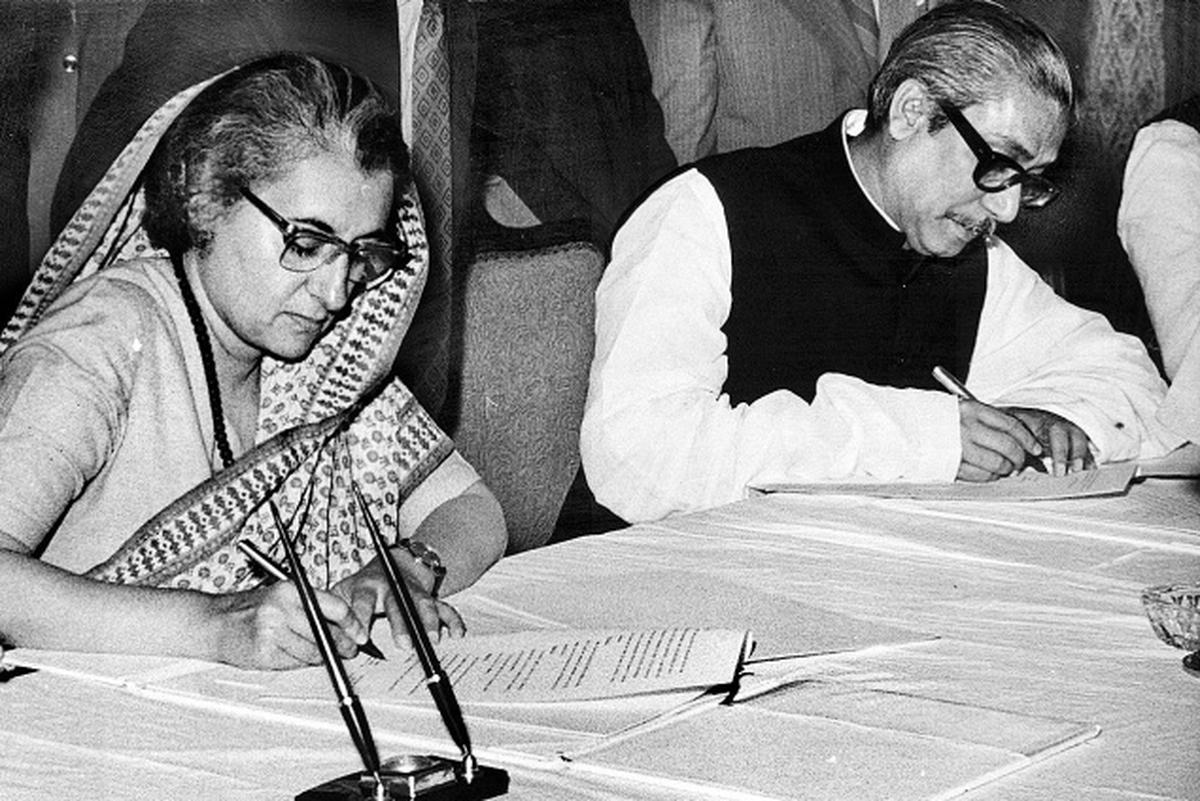

The immediate aftermath of independence revealed the scale of India’s ambitions. In March 1972, the 25-year Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Peace was signed. To many Bangladeshis at the time, weary from war, this treaty seemed a guarantee of security. But in truth, it was a leash disguised as friendship. It bound Dhaka’s foreign policy to Delhi’s orbit, limiting the newborn nation’s diplomatic freedom. Bangladesh could not pursue independent alliances without risking India’s displeasure. The country that had fought a bloody war to gain sovereignty suddenly found its sovereignty compromised by the very neighbor that claimed to be its liberator.

Economically, India wasted no time in turning Bangladesh into a captive market. The war had devastated industries, agriculture, and infrastructure. Instead of supporting Bangladesh’s rebuilding with fair trade and balanced cooperation, India ensured that trade deals were tilted heavily in its favor. Bangladeshi industries, struggling to stand on their own, were quickly flooded by Indian products. The trade imbalance grew, with Indian goods dominating markets while Bangladeshi exports faced restrictions and non-tariff barriers on the Indian side. India presented itself as an economic partner, but in reality it was ensuring Bangladesh’s dependency, stifling Dhaka’s capacity to build a competitive economy.

The issue of water exposed India’s true intentions even more starkly. Despite Bangladesh’s objections, India went ahead with the construction of the Farakka Barrage in the 1970s, diverting the flow of the Ganges for its own benefit. The result was disastrous for Bangladesh’s southwest region: salinity intrusion, reduced fish stocks, declining agricultural productivity, and ecological imbalance. India’s decision to prioritize its own irrigation and navigation needs over the survival of millions of Bangladeshis was a betrayal of the principles of cooperation and solidarity. The Farakka dispute became a symbol of India’s disregard for Bangladesh’s needs, a pattern that continued with the Teesta River and other transboundary waters. Promises of fair agreements were made repeatedly, but they were never honored, leaving Bangladesh hostage to India’s unilateral actions.

India’s involvement also seeped into Bangladesh’s politics in ways that undermined democracy. In the early years of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s government, Indian advisors and intelligence maintained an outsized presence in Dhaka. India supported Mujib not out of love for democracy, but because his leadership kept Bangladesh firmly aligned with Indian interests. When Mujib moved toward authoritarianism by introducing one-party rule through BAKSAL in 1975, India raised no objection. The silence was telling: Delhi did not care whether Bangladesh remained democratic or dictatorial, as long as it remained compliant. This set the tone for decades of Indian behavior—support for whichever leadership in Dhaka would keep ties tilted toward India, regardless of democratic legitimacy.

The border situation is another grim reminder of India’s double standards. While politicians in Delhi speak of friendship and shared sacrifice, India’s Border Security Force (BSF) has consistently committed violence against Bangladeshi civilians. Farmers, laborers, traders, even children have been shot dead on the frontier, often on flimsy accusations of smuggling. These killings expose India’s deep-seated mistrust and its willingness to treat Bangladeshi lives as expendable. Instead of a border of peace between two friends, India built a heavily militarized line of hostility. Decade after decade, the killings continued, eroding the myth of brotherhood.

After Mujib’s assassination, Bangladesh went through turbulent years, with different regimes trying to assert greater independence. General Ziaur Rahman and later General Ershad sought to diversify Bangladesh’s foreign policy, opening ties with China, Pakistan, and the United States to balance Indian influence. But India never allowed Dhaka to step too far. Economic leverage, geographical control, and constant diplomatic pressure kept Bangladesh from breaking free. Even when leaders tried to distance themselves from Delhi, they found themselves forced back into compromise. India’s dominance was like a shadow that never lifted.

The return of Sheikh Hasina in the 1990s marked a new phase in this story of dependency. Unlike her rivals, Hasina pursued close ties with India as the central pillar of her foreign policy. Delhi rewarded her loyalty, and in turn, India’s grip tightened further. Security cooperation became a central theme, with Bangladesh cracking down on insurgent groups that India accused of operating from its territory. While this directly benefited India, Bangladesh gained little on critical issues such as water sharing or trade. The Teesta agreement, for instance, has been promised for years but never delivered, blocked by domestic politics in West Bengal. Yet Hasina’s government has been unable—or unwilling—to challenge India strongly on this matter, leaving Bangladesh’s northern districts to suffer water shortages while Delhi continues to dictate terms.

Economically, Hasina’s era saw Bangladesh entangled in Indian-led infrastructure and energy projects, often financed on terms favorable to Indian companies. Transit facilities for Indian goods through Bangladesh were granted with little reciprocity. Trade imbalance widened as India’s corporations expanded their dominance. At the same time, non-tariff barriers prevented Bangladesh from meaningfully entering the Indian market. Bangladesh’s dependence deepened, while India reaped the profits.

Perhaps the most troubling aspect has been India’s role in legitimizing Hasina’s increasingly authoritarian rule. The 2014 and 2018 elections were marred by irregularities and accusations of rigging. International observers criticized them as unfree and unfair. Yet India stood firmly by Hasina, ensuring she faced little external pressure. Delhi’s calculation was simple: Hasina was a reliable partner who would never challenge Indian dominance. In return, India offered her political support, even if it meant undermining Bangladesh’s democracy. This mirrors India’s silence during Mujib’s authoritarian turn in the 1970s. The pattern is unmistakable: for India, democracy in Bangladesh matters only when it serves Indian interests.

All these threads lead back to the central truth: India did not help Bangladesh in 1971 out of altruism. It intervened to destroy Pakistan, to cement regional hegemony, and to create a dependent neighbor. The decades since have only reinforced this reality. From the Treaty of Friendship to Farakka, from border killings to trade imbalance, from propping up authoritarianism to blocking water agreements, India’s role has consistently prioritized its own interests at Bangladesh’s expense. The narrative of India as a benevolent savior is a myth that dissolves under scrutiny. What remains is the record of a neighbor that exploited Bangladesh’s birth to advance its own agenda.

For Bangladesh, this history offers a harsh but necessary lesson. Liberation was won through the blood of its own people, not as a gift from India. Independence must mean more than a flag and a national anthem; it must mean freedom from external domination. To achieve that, Bangladesh must shed the illusion of Indian goodwill and approach the relationship with realism, caution, and a determination to defend its own interests. Fifty years after 1971, the dark side of India’s role is too clear to ignore. India never wanted a strong, self-reliant Bangladesh; it wanted a dependent client state. Unless Bangladesh breaks this cycle of dependency, the promise of true independence will remain unfulfilled, trapped in the shadow of its overbearing neighbor.

আপনার মতামত জানানঃ